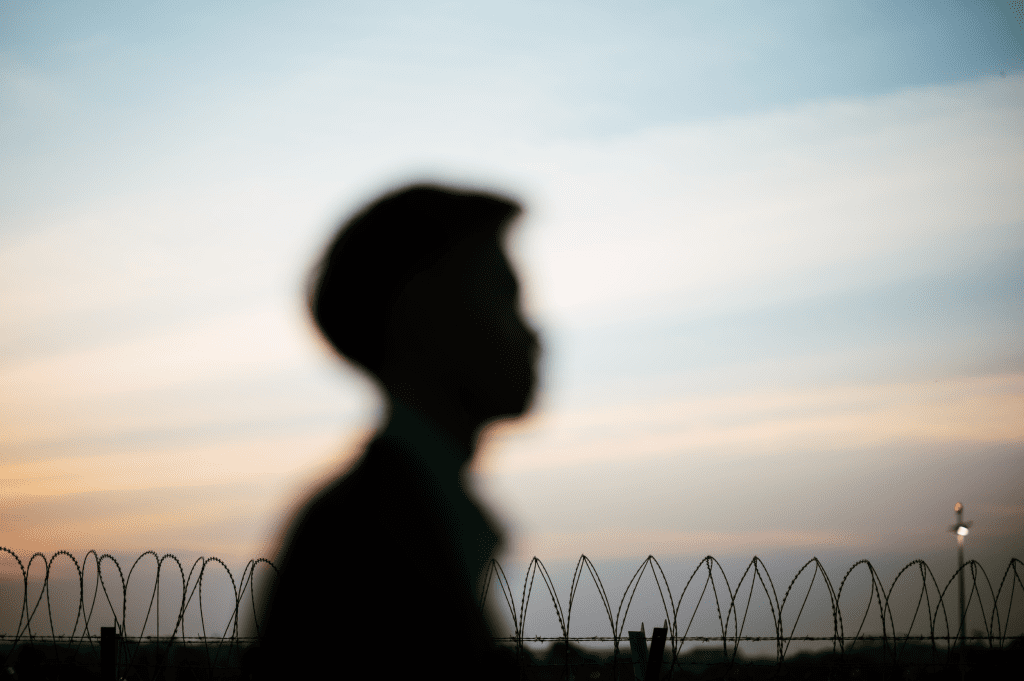

Explainer: Routine strip searching of kids in prisons

What is routine strip searching?

Routine strip searching involves forcing children as young as ten to remove their clothing in front of adult prison guards on a regular basis.

In most Australian states, overly broad laws permit the practice, with children often strip searched when they first enter a prison, after contact visits with family and after court appearances. What this means is that every time a child hugs their dad or holds their mum’s hand, they can be subsequently strip searched.

Data previously obtained by the Human Rights Law Centre has shown that children are being subjected to alarmingly high rates of strip searches. For example, in Tasmania, data showed that children were subjected to 203 strip searches over a 6 month period in 2018, with no contraband located. And in NSW, data showed over a 403 strip searches were conducted on children at two youth prisons over a one month period in 2018, with only one item – a ping pong ball – found as a result.

Why should routine strip searching be banned?

1. It’s re-traumatising and dehumanising

Being subjected to routine strip searching can be humiliating and degrading for any person, and is especially harmful to children given that a significant number of children and young people in youth prisons are also the victims of abuse, trauma or neglect. Forcing this cohort of children to routinely remove their clothes is invasive, harmful and unnecessary. This is particularly the case for girls in prison, many of whom have histories of physical and sexual abuse.

2. It’s unnecessary and ineffective

Evidence from Australia and around the world shows that routine strip searching does not have a deterrent effect, and that reducing strip searches do not increase the amount of contraband in prisons. For example, in the UK, the use of alternative search measures has not had any negative impacts on safety or security. [1] In the Australian context, the reduction in strip searching at two women’s prisons in Western Australia did not lead to an influx of contraband being brought into these facilities.[2]

3. Safer and more effective alternatives exist

There is no reason why governments across Australia continue to subject children to a practice that will likely scar them for life when they can instead use wands and X-ray body scanners, similar to those used in airports, to search a child when required. This is especially the case given that the NSW, Victorian and Western Australian Governments are already trialling these search practices in some adult prisons.

Governments must ban the routine strip searching of children

Laws should be amended to strictly prohibit the routine strip searching of children in prisons across Australia. Like best practice laws that exist in the ACT and the NT,[3] and consistent with international human rights standards that discourage the practice of routine strip searching,[4] a strip search should only ever be permitted as a last resort after all other less intrusive search alternatives have been exhausted and there remains reasonable intelligence that the person is carrying dangerous contraband. The reasons for any strip search, and the basis for forming having reasonable intelligence, must always be documented, in order to ensure transparency and accountability.

This explainer is not legal advice

The contents of this publication do not constitute legal advice, are not intended to be a substitute for legal advice and should not be relied upon as legal advice. You should seek legal advice or other professional advice in relation to any particular matters you or your organisation may have.

[1] See, eg, Lord Carlile, An independent inquiry into the use of physical restraint, solitary confinement and forcible strip searching of children in prisons, secure training centres and local authority secure children’s homes, 2006 The Howard League for Penal Reform, 173.

[2] See, eg, the Office of the Inspector of Custodial Services, Strip searching in Western Australian Prisons (March 2019) 9.

[3] Youth Justice Regulations 2006 (NT), r 74; Children and Young People Act 2008 (ACT) sections 254 and 255.

[4] United National Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules), rules 50-53.

Explainer: NSW’s proposed laws on hate crimes and places of worship

If passed, new laws in NSW would have wide-ranging implications for the right to peaceful assembly and may lead to the criminalisation of conduct which does not impact on the rights of people to practice their religion and be protected from racial or religious hatred.

Read more

Explainer: Making Queensland Safer Act 2024

The Queensland Crisafulli Government’s latest legislation, the Making Queensland Safer Act 2024 (Act), substantially changes how children are treated by Queensland’s police, courts and prisons, including by making prison sentences significantly longer. The Queensland Government concedes that the changes are ‘more punitive than necessary to achieve community safety’ and ‘in direct conflict with international law standards’. ¹

Read more

Explainer: Migration Amendment (Removal and Other Measures) Bill 2024

A legal explainer of the Migration Amendment (Removal and Other Measures) Bill 2024 , with a brief analysis of its operation. The Bill permits the Minister to direct certain people to take steps to facilitate their removal from Australia. It also prohibits nationals from certain countries from making a valid application for any visa to come to Australia.

Read more